By Quentin Goodbody

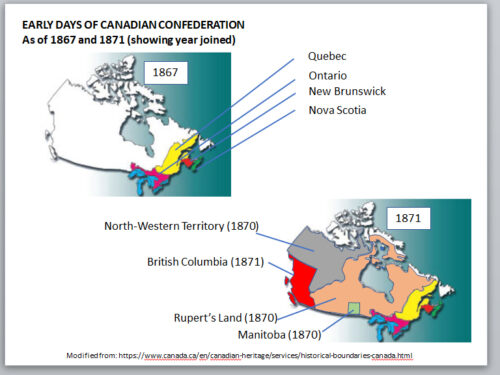

Most of us remember the big celebrations across Canada in 2017 to mark the 150th anniversary Canadian Confederation which occurred July 1st, 1867. We in BC joined in the party, but really this was eastern Canada’s celebration because BC did not become part of Canada until July 20th, 1871. This year marks our 150th anniversary!

The story of how BC came about, and how we ended up part of the Canadian confederation is all about colonial expansion. It has little to do with the First Nations who, after the fur trade days, became disenfranchised and were not afforded any political say.

Colonial expansion into North America arguably started with Columbus discovering the ‘New World’ in 1492 – which was promptly claimed by Spain. Portugal, the other major colonial power of the time, didn’t like that. According to the Treaty of Tordesillas signed in 1494 non-European lands west of a meridian about halfway between the Portuguese Cape Verde Islands and the newly discovered Caribbean islands would belong to Spain, while that east of the line belonged to Portugal. It was irrelevant that Spain and Portugal had no idea about much of the Americas. No one else paid any attention to this treaty, least of all England and the peoples inhabiting the affected lands.

Due to its isolation, the Pacific Northwest remained unmolested by outside influence until the late 18th Century when Russian, American and British fur traders encroached on Spain’s ‘rights. Meanwhile, Spain had been very busy plundering Central and South America since the early 1500s. In 1774 Spain sent Juan Perez up from their Pacific base of San Blas (in modern Mexico) to assess the degree of ‘incursion’ on Spain’s sovereignty. Perez visited Haida Gwaii and Nootka Sound. Captain Cook famously visited Friendly Cove in Nootka Sound in 1778 during his third Pacific voyage looking for the Northwest Passage: reports of his visit and rumours of large profits trading furs to China attracted more outsiders to the area.

Things started heating up in 1789 when the Spanish returned to Nootka, kicked the American fur traders out, arrested a British captain whose ship carried sufficient supplies to establish a settlement, and seized a number of other ships and their crews, bringing them back to San Blas. Spain established the short-lived colony of Santa Cruz de Nuca at Nootka and built Fort San Miguel there to cement their ownership of the area. Britain was NOT happy and a serious diplomatic squabble, called the Nootka Crisis, resulted. War was avoided, with Britain and Spain agreeing not to establish any permanent base at Nootka Sound, but ships from either nation could visit. They also agreed to prevent any other nation from establishing sovereignty. Spain’s intent was not to colonize the area but to use it as a buffer between encroaching Russian influence from Alaska and their more southern, lucrative colonies in Mexico, Central and South America. Spain effectively withdrew from the Pacific Northwest in 1794. Throughout all this, the First Nations had no understanding of what was going on.

Increased visitation by British and American traders followed who realised significant profits selling furs to Asia. Captain George Vancouver’s charting of the coastline in the early 1790s was one way of asserting British interests. The permanent British presence in the area came later with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) establishing a series of fur trading forts – Fort Simpson in 1831 (near present-day Prince Rupert) and Fort McLoughlin in 1833 (near present-day Bella Bella) – to intercept inland furs being traded with the Americans. In 1843 the HBC established a fort at Camosun on Victoria’s Inner Harbour: initially called Fort Albert, it was after some months called Fort Victoria.

The 1846 Oregon Treaty between the United States and Great Britain, which established the 49th Parallel as the official border between US and British interests, prompted the HBC to move its headquarters from Fort Vancouver on the banks of the Columbia River north to Fort Victoria on Vancouver Island. In 1849 the British Colonial Office designated Vancouver Island a crown colony and leased it to the HBC for 10 years at an annual fee of seven shillings with the intent that the HBC would encourage British settlement within five years. The idea was that this would halt the northern advance of American influence. That same year, the HBC established Fort Rupert in northern Vancouver Island – not so much for the fur trade – which was diminishing over time due to over-trapping – but because of the coal deposits there which had been known about since 1835. With the increasing use of steam vessels, coal became a valuable and strategic commodity. When the Rupert coal mines turned out to be a failure, attention switched to Nanaimo following First Nations reports of coal there in 1851. The establishment of coal mines at Nanaimo heralded the change from fur trading to a settler economy for the colony.

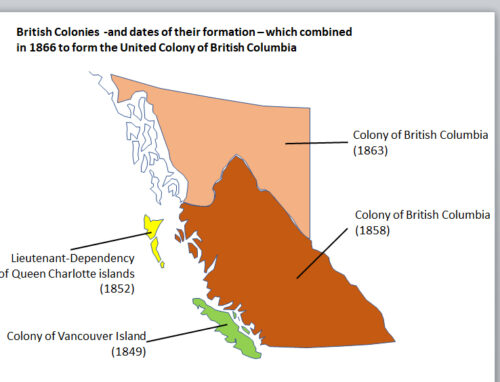

Following a gold rush on Moresby Island in 1851 which saw an increase in American presence, the British Colonial Office created the Colony of the Queen Charlotte Islands to emphasise British sovereignty. A similar gold rush incursion of Americans during the Fraser River Gold Rush of 1858 prompted the establishment of the mainland Colony of British Columbia, which was expanded to the north in 1861 in response to the Caribou Gold Rush. The three colonies were united in 1866 into the ‘United Colony of British Columbia’ which had the outline of our current province.

The U.S. purchase of Alaska from the Russians in 1867 sandwiched the United Colony of British Columbia between American territories. Britain and the new Canadian confederation formed July 1st, 1867 consisting of Ontario, Quebec (prior to Confederation known jointly as The Province of Canada), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, became concerned about the Pacific Northwest being annexed by the Americans. It was so very far away – Britain could not reach the colony without either sailing around Cape Horn or the Cape of Good Hope. However, the Americans could get there quicker: construction of the first transcontinental railroad in the U.S. – the Central and Union Pacific connecting San Francisco to Saint Louis – was commenced in 1864 and completed in 1869. Construction of a second U.S. transcontinental railway, the Northern Pacific, started in 1870. At this time, the U.S. definitely had their eye on Britain’s Pacific Northwest. A report submitted to the US Senate Committee on Pacific Railroads in February 1869 stated: “The opening by us first of a North Pacific railroad seals the destiny of the British possessions west of the 91st meridian. They will become so Americanised in interests and feeling that they will be in effect severed from the new Dominion, and the question of their annexation will be but a question of time.”

Needless to say, Britain and Ottawa, wanting a British dominion stretching from the Pacific to the Atlantic, were extremely uncomfortable with this. During 1870 the Canadian Confederation was extended west through the incorporation of Manitoba (in its original form), and the HBC domains of Rupert’s Land and The North-Western Territory. The United Colony of British Columbia, crippled by debt and seeing confederation as a means to support, agreed to join Canada on July 20th, 1871. BC wanted a wagon road connecting to the east, but Ottawa offered something much better – a railroad. Article 11 of the Terms of Union, reads in part: “The Government of the Dominion undertake to secure the commencement simultaneously, within two years from the date of the Union, of the construction of a railway from the Pacific towards the Rocky Mountains, and from such point as may be selected, east of the Rocky Mountains, towards the Pacific, to connect the seaboard of British Columbia with the railway system of Canada; and further, to secure the completion of such railway within ten years from the date of the Union.”

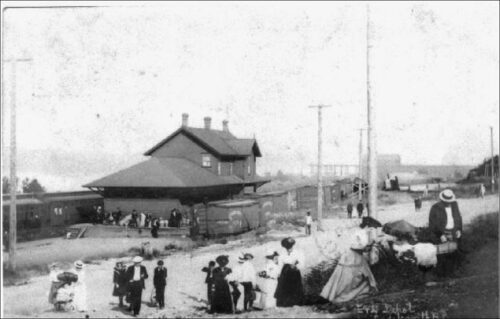

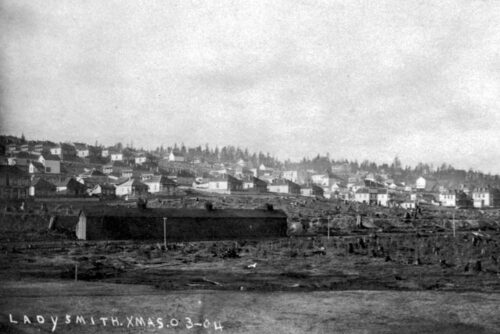

This was a tall order – hugely expensive, and a massive engineering challenge. Also, there were questions of the route of the railway and where the Pacific terminus would be. Ultimately, of course, the railway was built, but much later and not without a lot of squabbling, threats by BC to withdraw from the Confederation, and possibly some underhand dealing. It also did not take the expected route or end up with either of the proposed termini – but this is another chapter in our story – one which you can hear in an upcoming Historical Society talk on Zoom July 20th titled “Construction of the E&N Railway: Ladysmith’s role, and the History of our Railway Station”.

An open house at the railway station is planned for Wednesday, July 21, 2021, from 4pm to 7 pm so our community can judge what non-profit use the building can best be put to. Do come!