Cassidy Aquifers

To aid public discussion regarding concerns about risk of contamination of groundwater in the Cassidy area posed by ongoing industrial activity, TAKE 5 is presenting a two-part article on the Cassidy Aquifer issue written by Dr. Quentin Goodbody.

By Dr. Quentin Goodbody

In this first part of the Cassidy Aquifers article, we will take a closer look at what has happened to date and speculate about what regulatory activity may occur in the future. The purpose of this two-part article is to aid public discussion regarding concerns about risk of contamination of groundwater in the Cassidy area posed by ongoing industrial activity.

Background

In 2011, Schnitzer Steel Canada took over its current site just south of Nanaimo Airport, where it conducts End of Life Vehicle (ELV) processing and other scrap metal recycling. In 2013, the company removed contaminated soil left from previous operators; the site had been used for auto wrecking and metal recycling since the 1950s, long before the introduction of land use zoning in 1987 through passage of CVRD Electoral Area H Zoning Bylaw No. 1020.

Though the site is now zoned I-1, which does not permit auto wrecking and metal recycling, the BC Local Government Act permits land uses that were lawful prior to the introduction of land use zonation to continue as a non-conforming use — providing there is not a six-month break in operations and the operations retain the same scale and scope as prior to the introduction of land use zonation.

In 2016, Schnitzer — on behalf of its landlord, Cassidy Sales and Service Ltd. — filed an application (No. 03-H-16RS (PID: 008-903-603)) with the CVRD for rezoning of the site to I-4 (Industrial Recycling), to accommodate auto recycling, metal recycling activities and exterior storage, which are not permitted under I-1 zoning.

Before and since that application, much concern has been expressed by the public regarding the scale and aesthetic impact of the recycling operations and the risk of contamination to the underlying aquifer that these operations pose.

Acceptance by both Schnitzer and the CVRD of the reality of risk to the aquifer is implicit in actions taken by both since the rezoning application was made. Schnitzer implemented measures to avoid ground contamination by storm runoff from its operations: extensive concrete slabs were installed to floor those areas where ELVs and non-ferrous metals are processed, with runoff from these slabs being directed towards catchment basins for treatment. Regular maintenance procedures were adopted to ensure the continuing functioning of this catchment system.

In 2017, discussions were initiated regarding a legal covenant aimed at mitigating the threat of groundwater contamination by enforcing such preventive measures.

In 2018, the CVRD drafted and gave first and second readings to bylaws 4194 and 4195 to accommodate rezoning of the Schnitzer site from I-1 to I-4, with allowance for ELV processing and metal recycling.

Meanwhile, discussions on the covenant continued: In 2021, as a pre-requisite step to re-zoning and to holding a Public Information Meeting regarding the rezoning application, the CVRD presented a draft of the covenant for adoption with wording to ensure that so long as scrap metal and ELVs are collected, stored and dismantled on the Cassidy site, specific measures were in place to protect the sensitive underlying aquifer, including hard surfacing, drainage collection and oil separators, and mandatory monitoring well test reports.

After much consultation, on May 3, 2023, the CVRD Electoral Area Services Committee (EASC) was advised that the applicants were in agreement with the wording of the covenant. At that same meeting, the EASC voted to recommend to the CVRD Board that the re-zoning application be denied. Citing uncertainty regarding implications stemming from rejection of the rezoning application, EASC also voted that staff consult with legal counsel on any potential technical issues regarding the denial of the application and report back prior to the May 10, 2023, CVRD Board meeting.

At the May 10, 2023, CVRD Board meeting, the Board reported on a motion adopted in closed discussion that a Public Information Meeting regarding the application be held in June 2023 in accordance with CVRD Development Application Procedures Bylaw 2022, given that the applicants had agreed to the proposed covenant. CVRD staff were also asked to provide the Electoral Area Services Committee with a report summarizing the questions and comments recorded at the upcoming Public Information Meeting as well as provide complete documentation regarding the application.

The Public Information Meeting was held June 19, 2023, in the Aggie Hall, Ladysmith. Ninety-seven members of the public attended, along with extensive representation from the CVRD. Presentations were made by both the CVRD and Schnitzer regarding the rezoning application. A large number of questions from the public were addressed by the CVRD and Schnitzer. A report on this meeting has since been provided by CVRD staff to the CVRD Electoral Area Services Committee. What remains to happen now is a CVRD Board ruling on the rezoning application.

In addition to the above activities, in June 2022, a civil lawsuit was initiated against Schnitzer alleging violations of CVRD land use zoning bylaws and against the CVRD alleging failure to enforce its own land use bylaws.

What’s Happening Now

Schnitzer Steel continues its operations located on top of the Cassidy high vulnerability Aquifer 161 and also continues to take steps to avoid ground water contamination from these operations. Regular maintenance of catchment systems for runoff from concrete pads flooring ELV processing and metal recycling areas is performed to ensure their proper function. Water from five wells on the property are monitored regularly to determine if ground water contamination is occurring.

The CVRD informs that there is no anticipated timeline for moving forward towards a decision on the rezoning application. Interaction with the Regional District of Nanaimo, Island Health and relevant sections of the BC Provincial Government will likely occur prior to a final decision by the CVRD Board.

Monitoring of surface water quality in a stream nearby Schnitzer’s property (Thomas Creek) is ongoing. The CVRD’s intent is to establish a network of monitoring stations throughout the region; however, staffing shortages are hampering progress on development of CVRD “in-house” best practices for groundwater management.

Speculation on What May Happen

Schnitzer theoretically could withdraw their rezoning application, trusting that their current operations be determined legal non-conforming. Such would allow for continuation of their activities.

If the CVRD Board approves the rezoning application, absent of any legal directive to the contrary, the current scope and scale of Schnitzer’s existing operations could continue with the company adhering to the terms of the covenant.

Denial of the rezoning application by the CVRD Board would probably trigger an assessment of whether Schnitzer’s current operations are legal non-conforming or not. If they are considered legal non-conforming, then Schnitzer could continue with the scale and scope of its current operations. If they are not, then proceedings relating to land use violations would likely commence; options facing Schnitzer in this scenario would appear to be to either scale back to that level of legal non-conforming activity permitted by the Local Government Act, or move their operations to another suitably zoned location. Given the scale of their investment in the Cassidy property, this appears something the company would be reluctant to do.

Any continuation of Schnitzer’s activities at Cassidy will not satisfy those who feel that the siting of industrial activities considered to pose a contamination risk on top of an important high vulnerability surface aquifer is inappropriate. Focus would turn towards the ongoing civil suit.

Cassidy Aquifers, how they formed and how they work Part 2

Cassidy Aquifers 101

All our fresh water ultimately comes from rainfall. If we do not collect rainwater directly from our roofs, we access fresh water in one of two ways:

The simplest way of getting water is by drawing or pumping it directly from a nearby lake, river, stream or spring. The Town of Ladysmith, Diamond Improvement District, Stz’uminus First Nation and Saltair all draw water from two stream-fed artificial lakes (reservoirs) in the hills west of Ladysmith – Holland Lake and Stocking Lake. A lot of money has recently been spent on filtration systems to ensure that the water from these reservoirs is clean enough for domestic consumption.

However, if you live in the surrounding district, chances are that you do not have a body of surface water from which you can draw, nor do you have access to a municipal water system. Instead, you have to go looking for water in the ground – in other words, you must find an aquifer. When you find one, you want the water you take from it to be uncontaminated so you can use it in your home: there are all sorts of protocols associated with water well completion to ensure this.

Aquifers are not underground rivers or water-filled caverns. They consist of rock or unconsolidated sediment such as gravels and sands which hold water in spaces between the mineral grains making up the rock or sediment. These often tiny spaces are collectively called Porosity, which typically makes up 10-20% of the bulk volume of a rock aquifer, but can be more than 30% in unconsolidated sediments.

Just holding the water in the pore spaces is not enough for an aquifer to be useful. The water must be able to move through the rock or sediment so we can get it out. This property is called Permeability. The degree of permeability depends on the level of connectedness between the pores in the rock or sediment (Figure 1).

The more porosity and permeability there is, the faster water can move through the medium, and the higher the rate water can be sustainably produced from a well dug or drilled into it.

For an aquifer to provide a stable supply for water, the rate of natural fresh water recharge to the aquifer must equal or exceed the rate of water withdrawal from pumping wells. If this is not the case, the water level in the aquifer will go down and wells may become dry because they are not deep enough to encounter the modified (deeper) groundwater level.

Geology of the Cassidy Area Aquifers

Geology refers to the rocks and unconsolidated sediments that make up the ground we walk on.

The geology of the Cassidy area has been determined by mapping the rocks and sediments at ground surface and getting an idea of the subsurface set-up through examination of the logs of over 2000 water wells drilled in the area. Several aquifers have been recognised in the Cassidy area which are currently being used for domestic, agricultural and industrial purposes. The following description of the geology and the aquifers comes from a number of scientific reports that can be found online (references can be provided on request to the author).

There are two types of aquifers in the Cassidy area: 1/. Bedrock – composed of 80 million year old Cretaceous sandstones which have low to moderate porosity and permeability from which wells generally produce water at low rates. 2/. 12000-14000 year old unconsolidated sands and gravels lying on top of the Cretaceous bedrock which are much more porous and permeable and from which water can be produced at higher rates.

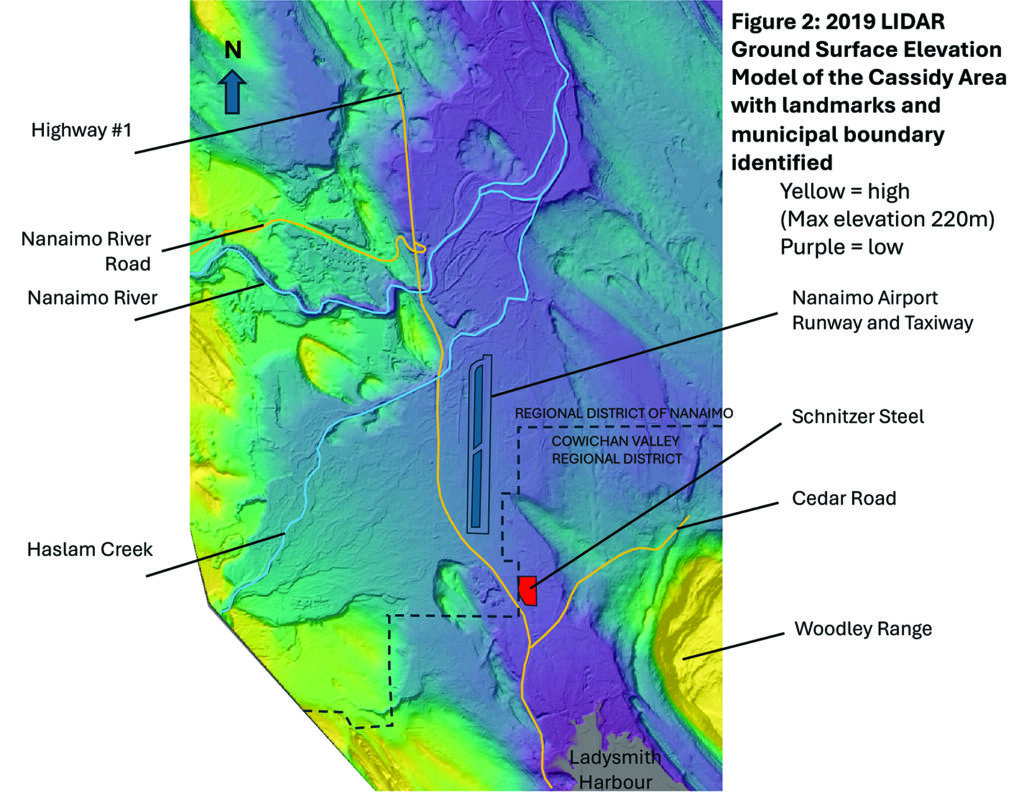

Whereas the ground surface in the vicinity of Cassidy and The Nanaimo Airport is essentially flat today (Figure 2), geological mapping of the top of the Cretaceous bedrock reveals a valley system which was eroded into it during and just after the last glacial period about 14,000 years ago.

This ‘fossil’ valley system extends from Ladysmith Harbour north toward where the Nanaimo River now flows to its estuary in Nanaimo Harbour (Figure 3).

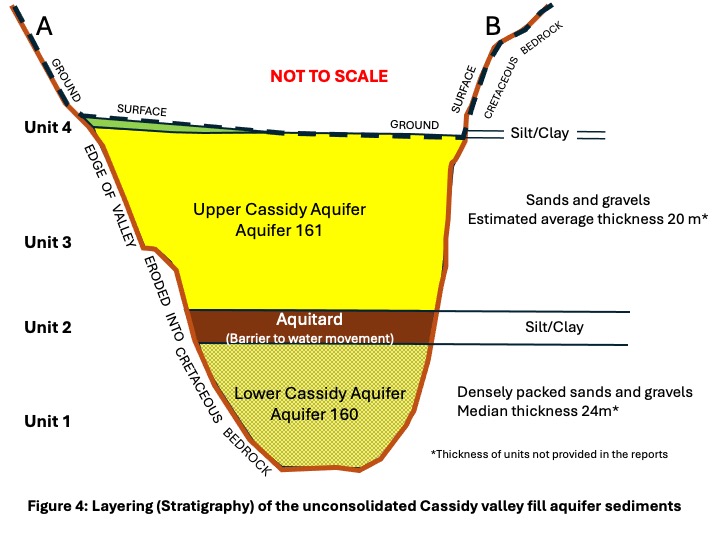

Glacially fed streams filled this ‘fossil’ valley system with unconsolidated sediment. There is a distinct layering (stratigraphy, in geologic terms) to this valley fill (Figure 4).

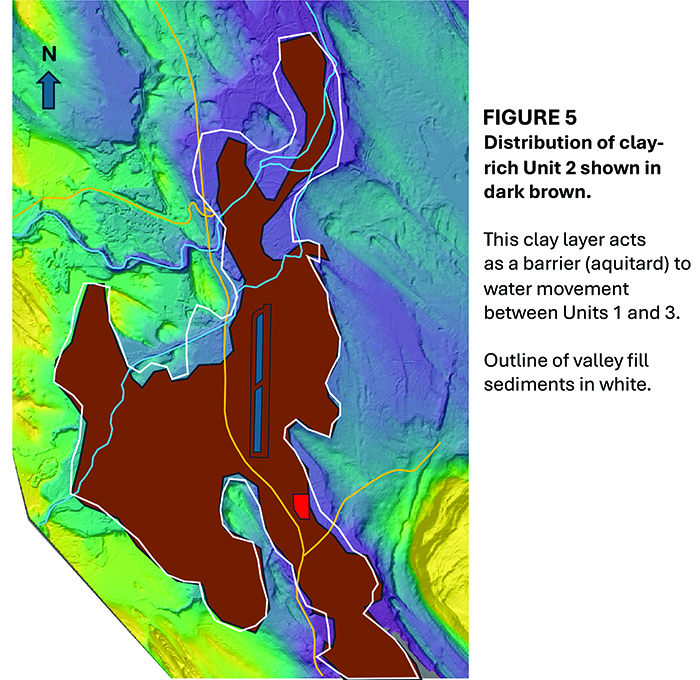

The aerial distribution of each layer (stratigraphic unit) is shown in Figure 5.

Unit 1, the oldest and deepest part of the unconsolidated valley fill, consists of densely packed sands and gravels with moderate porosity and permeability. These are distributed only locally in the deepest portion of the fossil valley and lie directly on Cretaceous bedrock.

Unit 2, distributed over the entire valley system, consists of impermeable claystones deposited some 12000 years ago when sea level was about 150 meters higher than present.

Unit 3, distributed over much of the buried valley system, consists of loosely packed highly porous and permeable sands and gravels. These are exposed at ground surface except for a small area north and west of the airport.

The impermeable clay-rich Unit 4 is ground surface to a small area underneath and west of the airport. It locally forms a barrier to surface water movement into the underlying sands and gravels of Unit 3.

Hydrogeology of the Cassidy aquifers

Hydrogeology refers to the movement of water within rocks and sediments.

The Cassidy area lies within the watershed of the Nanaimo River, which includes the Nanaimo River and its major tributaries such as Haslam Creek (Figure 6).

The majority of the watershed lies within the Nanaimo Regional District (NRD); the southernmost part of the watershed, including part of the Cassidy area, lies within the Cowichan Valley Regional District (CVRD).

Analysis of groundwater levels in observation wells provides some understanding of how water flows into and out of the various geologic units.

The Cretaceous bedrock of the area is an important aquifer to those living outside of the distribution of the fossil valley-fill sediments. The BC Provincial Aquifer database recognises two bedrock aquifers, numbered 162 and 964; the boundary between the two is roughly along a line continuing northwest parallel to the north shore of Ladysmith Harbour with 964 being west of this line and 162 east of it. Groundwater recharge for both aquifers is direct from rain, but due to the bedrock’s limited permeability and porosity it appears to be slow and care has to be taken not to over-produce from wells and running them dry. Fractures associated with faults in the bedrock appear to be an important factor in locally higher well production rates.

The water-bearing densely packed sands and gravels with moderate porosity and permeability of Valley-fill Unit 1 are numbered Aquifer 160 in the B.C. Provincial Aquifer database. There are relatively few well penetrations because it underlies a shallower good aquifer (Unit 3). Recharge occurs after a week’s lag following rainfall which indicates groundwater flows into it either from the underlying bedrock or via a slight connection to the overlying aquifer Unit 3. Aquifer 160 is termed a ‘confined’ aquifer due to its not being exposed at ground surface and because it is everywhere overlain by the impermeable claystone Unit 2. Only a few wells produce from aquifer 160; their low volume of production appears to have minimal effect as observation wells appear stable over time, the most recent data reviewed being from 2016.

The clay-rich ‘tight’ (ie non porous and impermeable) Unit 2 acts as a barrier to groundwater movement between Units 1 and 3 and is scientifically termed an ‘aquitard’.

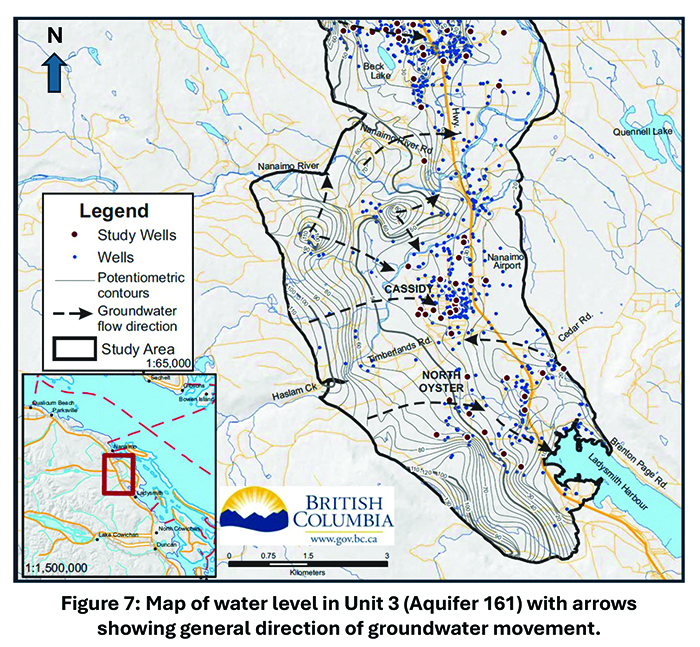

Valley-fill Unit 3, numbered Aquifer 161 in the B.C. Provincial Aquifer database, is the most important aquifer in the area. Its high porosity and permeability sands and gravels provide good well flow rates. This aquifer is termed ‘unconfined’ due to its being exposed at the ground surface. While groundwater recharge is mainly direct from rainfall in the watershed, local recharge from streams has prompted its division into two connected aquifers (Figure 5iii) – Cassidy Aquifer 1 to the south which is locally recharged by Haslam Creek, and Cassidy Aquifer 2 in the north which is strongly influenced by the Nanaimo River. The strong recharge in the north from the Nanaimo River facilitates bulk water extraction for industrial purposes by Harmac. Data suggests that groundwater pumping significantly affects water levels in Aquifer 161. Proximity to recharge sources, such as the Nanaimo River, locally allows for a stable high rate extraction, but more work with up to date information for the southern Cassidy Aquifer 1 (most recent data seen by the author dates from 2016) is required for determination of how much water can be taken from this aquifer without long term decline in groundwater water levels occurring.

Except where locally overlain by the impermeable clay-rich Unit 4, the sands and gravels of Unit 3/Aquifer 161 are exposed at ground surface beneath a variable soil cover.

The regional map of groundwater elevations in wells in Aquifer 161 (Figure 7) indicates that, on average, groundwater flows from the uplands west of Cassidy and diverges from the central Cassidy area, northeastward towards the Nanaimo River and estuary, and southeastward toward Ladysmith Harbour. However, this regional picture may be locally modified by production from water wells – as extraction of water from a well reduces the pressure around that wellbore and prompts groundwater movement toward it. This can cause local ground water movement against the regional flow.

More detailed analysis of many wells in the area is required to determine whether this aquifer is being over-taxed by the current level of withdrawal from wells or not, and how surface contamination might travel within the aquifer.

Aquifer Vulnerability and Industrial Activity

Increased land development pressures in the early 2000s, coupled with industrial and agricultural land use activities that were considered to potentially threaten the quality of ground and surface water, prompted the CVRD to participate in a multi-year study which focussed on assessing the relative vulnerability of groundwater resources to surface contamination on Vancouver Island. This study was conducted jointly by the BC Ministry of Environment, Vancouver Island University, Natural Resources Canada, The Vancouver Island Health Authority and the Regional Districts on Vancouver Island. A rating system, called by the acronym ‘DRASTIC’ (relating to seven significant factors taken into account) was devised; each recognised aquifer was assigned a vulnerability rating of either Low, Moderate or High. A vulnerability map for surface aquifers on Vancouver Island was produced that shows high vulnerability in the Cassidy area (Figure 8).

Of the Cassidy area aquifers:

Cretaceous bedrock aquifer 162 which outcrops over a wide area was considered of High Vulnerability to surface contamination entering via exposed high permeability fractures.

Although also recognised as possessing highly permeable fractured zones, Bedrock Aquifer 964 was rated of Moderate Vulnerability as it only locally outcrops at surface.

The unconsolidated confined Aquifer 160 (valley-fill Unit 1) is considered to have Low Vulnerability to contamination from surface sources as it does not outcrop at surface and is everywhere overlain by the aquitard Unit 2.

Aquifer 161 (valley-fill Unit 3), the porous and permeable sands and gravels of which are at ground surface over much of the Cassidy area, is considered of High Vulnerability to surface contamination.

The quoted vulnerability study also provided an example of appropriate hydrogeological assessment for development permit applications situated on various aquifer types. If Schnitzer’s Cassidy activities, which are located on top of High Vulnerability Aquifer 161, are considered as a commercial ‘junk yard’ and of moderate hazard for surface contamination, the following were deemed required for assessment of an application to conduct these activities at that location:

- a detailed groundwater site investigation including an ongoing monitoring program

- specifics of the potential contaminants (toxicity, quantity, transport behaviour),

- details on the protection design factors (natural attenuation, physical barriers, etc.)

- A detailed emergency response plan

- An assessment of the financial capacity of the responsible party to enact the plan.

However, if Schnitzer’s activities are considered as an industrial activity posing a high risk of surface contamination to the aquifer, the possibility of complete prohibition of those activities is cited.

What the Neighbours Think

The southern portion of Aquifer 161 straddles the boundary between the regional districts of Nanaimo and the Cowichan Valley, with Schnitzer’s activities being located immediately adjacent to the boundary on the CVRD side. Given the high permeability of Aquifer 161 and its deemed High Vulnerability to surface contaminants, it seems reasonable to assume that the Regional District of Nanaimo (RDN) is interested in what the CVRD decides regarding Schnitzer’s rezoning application. ‘Actions and Best Practices’ cited from a 2010 RDN “Groundwater Assessment and Vulnerability Study” by GW Solutions Inc. indicates that industrial activities in a high vulnerability aquifer zone are not recommended and that auto-wreck yards are not allowed in such zones.

Thank you to Dr. Quentin Goodbody for this explanation of how aquifers work.

Information Sources for Cassidy Aquifers

Barroso, S., R. Ormond, and P. Lapcevic (2016). Groundwater quality survey of aquifers in South Wellington, Cassidy and North Oyster, Vancouver Island. Prov. B.C., Victoria B.C., Water Science Series 2016‐05.

CVRD April 11th 2018: CVRD Bylaw No. 4194 – Electoral Area H – North Oyster/Diamond Official Community Plan Amendment Bylaw (13271 Simpson Road), 2018.

CVRD April 11th 2018: CVRD Bylaw No. 4195 – Electoral Area H – North Oyster/Diamond Zoning Amendment Bylaw (13271 Simpson Road), 2018

CVRD: May 3rd 2023: Staff Report to Electoral Area Services Committee Meeting from Community Planning Division, Land Use Services Department re: Application No. 03-H-16 S (PID. 008-903-603/Schnitzer Steel) plus attachment A: Draft Covenant and Schnitzer Steel Canada Ltd. Cassidy Facility Stormwater Maintenance Plan for Equipment maintenance and ELV Concrete Slab.

CVRD: May 3rd 2023: Electoral Area Services Committee Meeting Agenda and Minutes

CVRD: May 10th 2023: Minutes of the Regular meeting of the Board of the Cowichan Valley Regional District held in the Board Room, located at 175 Ingram Street, Duncan BC, on Wednesday, May 10, 2023 at 1:32 PM.

CVRD: July 19th 2023: Agenda of The Electoral Area Services Committee Meeting of July 19th 2023: Item 7: Information: Public Meeting Minutes Re: Application No. 03-H-16RS (Schnitzer Steel) – June 19, 2023.

Government of British Columbia: Ground Water Wells and Aquifers

https://apps.nrs.gov.bc.ca/gwells/aquifers

GW Solutions Inc. August 2017. STATE OF OUR AQUIFERS. Regional District of Nanaimo Aquifer 160. Report prepared for The Regional District of Nanaimo

GW Solutions Inc. August 2017. STATE OF OUR AQUIFERS. Regional District of Nanaimo Aquifer 161. Report prepared for The Regional District of Nanaimo

Liggett, J., Gilchrist, A. 2010: Technical Summary of Intrinsic Vulnerability Mapping Methods in the Regional Districts of Nanaimo and Cowichan Valley, Geological Survey of Canada, Open File 6168, 64 p.

Liggett, J., Lapcevik, P., Miller, K. 2011. A Guide to the Use of Intrinsic Aquifer Vulnerability Mapping. Report to the CVRD on the work of the Vancouver Island Water Resources Vulnerability Mapping Project., 60 p.

Take5 June 2023: 5 Minute Read: Cassidy Aquifer: https://issuu.com/take5publications/docs/online_take5_june_23.indd/s/25414243

Thurber Engineering Ltd: 2007. City of Nanaimo Engineering & Public Works Department Cassidy Aquifer Water Balance Study Completion Report.

Town of Ladysmith 2023: https://www.ladysmith.ca/sustainability-green-living/sustainability-program/watershed-protection

Waterline Resources Inc. 2013: Phase 1 Water Budget Project: RDN Phase 1 (Vancouver Island) submitted to the Drinking Water and Watershed Protection Technical Advisory Committee pages 160-190: Water Region # 6 – Nanaimo River.