In March of 1912, Ladysmith was booming. Copper ore from Mt. Sicker was being transported by train to the Tyee Smelter. Victoria Lumber And Manufacturing Company (V.L. &M) had opened new camps in the hills behind near Stocking Lake and the E&N Railway was in the process of extending their rails all the way to the Alberni Valley. Fishing and oyster farming competed with coal ships in Oyster Harbour, and Saltair was becoming the ‘fruit basket” for Vancouver Island. In addition, Canadian Collieries, who had taken over the mining interests of unpopular Robert Dunsmuir in 1910, announced that the Extension coal seam extended almost to the town’s front door. With Ladysmith’s population closing in on 5000, a state of the art hospital had been completed the previous year and a new high school was planned on Spion Kop overlooking Market Square. Indeed, the future for the new town looked bright.

Nowhere in the town was there more optimism than on First Avenue. The Victoria-Nanaimo road, completed in 1884, crossed over Holland Creek and skirted the town on its western boundaries (near where Ladysmith Secondary and the Frank Jameson Centre are located today). It then continued north past Grouhel’s farm, winding down Cemetery hill and out Benton Crossing to Nanaimo. In 1902, the road was redirected to enter Ladysmith at First Avenue. According to Richard Goodacre (1980) this resulted in,

”Shifting the centre of gravity of Ladysmith… the Nicholson Block, the Carlisle Block, the Campbell Building and the Stevenson Block went up quickly and defined the commercial centre of the town.”

Dunsmuir had ordained that his employees must live in Ladysmith and not at the mine head. As a result, most of the merchants had to pack up their businesses and follow their customers to Ladysmith. Homes, shops, hotels and even churches were quickly dismantled, loaded on flat cars and transported by rail from Wellington and Extension to Ladysmith. A narrow gauge railway was constructed up White Street to Third Avenue, and the buildings were winched up the hill by a donkey engine. Once in place, they were quickly reassembled. In some instances, the whole process took less than two days! These buildings were often flimsy wood constructions equipped with coal fires, wood stoves and gas lamps to serve the needs of their occupants.

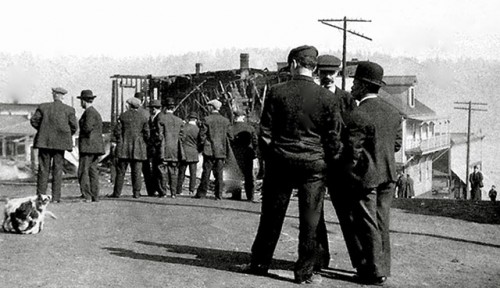

Thus, no one was too surprised when the fire bell rang out at 2 o’clock on Thursday morning, March 21, The Chronicle later reported that Tom O’Connell, the night watchman had given the alarm after spotting flames coming through the windows of the Masonic Hall on Gatacre Street. In a short space of time, the volunteer fire department arrived and played a hose on the rapidly growing fire, but it was far too late to save the building. They then turned four streams of water on the surrounding structures, but the Campbell building was already burning fiercely and the fire had spread to the Bickle Block as well. The firemen then worked desperately to prevent the fire from spreading east down Gatacre to the Jones Hotel and the Leiser building, and in the west from ‘jumping’ across First Avenue to the Europe Hotel. Meanwhile, hundreds of spectators, many in their nightclothes, stood by and watched the hard pressed volunteers battle the conflagration.

The actual cause of the fire was never determined, but the subsequent report to City Council by Fire Chief Michie drew attention to “the dangerous habit of storing gasoline and other combustibles within buildings in the downtown area.” The Chronicle also reported that only St. John’s Masonic Lodge # 21 had carried full insurance (perhaps due to the fact that their original hall in Wellington had previously been destroyed by fire.) Indeed, the Masons immediately began the construction of the sturdy brick building that is still in use today. In the aftermath, prominent city entrepreneur Mr. J.A. Knight decided to move his expanding business up the street to Lot 10, Block 9 at the corner of Gatacre and First; however, the Fire Wardens insisted he built a fire wall in accordance with the new City Fire Bylaw. Ladysmith would rebuild, but 1912 also marked the beginning of other problems for the fledgling community that would prove harder to extinguish.

[Note: The Stevens Block (later Geering’s) on the opposite corner of Gatacre and First went up in flames on Christmas Eve, 1973. The Knight Building burned to the ground in 1981, leaving only a clock to remind us of this very important business in the history of Ladysmith.]

Ed Nicholson, Ladysmith Historical Society.