On September 10, 1915, a brief item appeared in the New York Times under the heading

MINE OFFICIALS INDICTED

Charged with Manslaughter as Result of British Columbia Accident

The article went on to say that the Attorney General of British Columbia had the day before laid indictments for manslaughter against Thomas Graham, Chief Inspector of Mines for the province and John H. Tonkin, Managing Director of Pacific Coast Coal Mines Ltd. Both men were charged with carelessness in connection with “the disaster that caused the loss of nineteen lives by drowning at the Reserve mine near Nanaimo on February 15, 1915.”

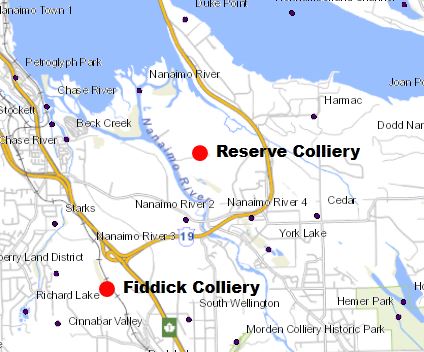

The newspaper item was wrong on two accounts. First the date of the drowning accident was on February 9th, six days earlier, and secondly, this accident did not occur at the Reserve mine at all. The Reserve Colliery, owned by the Western Fuel Company of Nanaimo was located on the Nanaimo River delta almost 2 miles northeast of the site of this disaster. The accident occurred at the former South Wellington Colliery now referred to as the Fiddick Colliery owned by the Pacific Coast Coal Mines company situated about a mile northwest of the outlet of Beck Lake at South Wellington.

The confusion in collieries no doubt arose from the fact that only three months after the South Wellington accident a second disaster did occur at the Reserve Colliery. On May 27, 1915 an explosion in the shafts of the Reserve mine resulted in the deaths of twenty-two men.

In its seemingly inhuman obsession with statistics, the Minister of Mines Annual Report indicated that fatalities in and around coal-mines during 1915 totalled fifty-two, the largest number in any year since 1909, due primarily to the accidents at South Wellington and the Reserve shafts. The ratio of fatal accidents for the year per 1,000 persons employed was 10.42. This was compared with a ratio of 2.97 per 1000 for 1914; the ratio for the last ten year period being 4.73 per 1000 persons. In 1915 there were 4,991 persons employed in and about coal mines in the province.

History of the South Wellington (Fiddick) Colliery

The Fiddick Colliery was somewhat unique amongst Vancouver Island coal mines in that it came into being as a result of the Settlers Rights Act of 1904. Under this legislation, settlers “who could show occupation and improvement of lands within the railway belt (the 20 miles on either side of the E&N Railway line, reserved to the railway) prior to enactment of the Settlement Act of 1884, and who applied to the Lieutenant Governor in Council in the year following the 1904 Act, were granted the right to obtain Crown grants “in fee simple” (i.e. full title to the land, including all mineral and timber rights)”.

James Dunsmuir, as owner of the E&N Railway unsuccessfully challenged the ruling but in 1905 was granted other lands at the north end of the railway belt as compensation for those lost. This was the same year that he sold the E&N railway to the CPR however he retained all the coal mining interests originally granted within the railway belt to his father, Robert for building the railroad.

Following the passage of the Settlement Act an enterprising entrepreneur and former Mayor of Winnipeg, John Arbuthnot through various deals with the original settlers or pre-emptors was able to acquire the rights to mine huge coal reserves now included in these fee simple titles. He also acquired mining rights north of the railway belt at Suquash near Port Hardy through his lumber interests in that area.

Arbuthnot moved to Victoria in 1907 with his family and purchased the Robleda estate on Rockland Avenue next door to Government House. Setting up offices in the Metropolitan Building at the corner of Government and Courtenay Streets from which to run his lumbering and soon to be coal mining interests he quickly entered the inner circle of Victoria’s wealthy elite believing the city to be a good place for a man with money to invest. He could see the attraction of the city as a winter resort and predicted a big influx of people from the East, particularly from the Dominion prairie provinces. Serving on various committees in the city including becoming chairman of the Parks committee, he was also deeply involved in a number of the pastimes of the rich such as auto racing and yachting.

Arbuthnot’s first venture into coal mining on the island was the establishment of the South Wellington Colliery in 1907 situated on the Fiddick and Richardson properties at South Wellington. At first the company was almost a family affair, the directorship composed of people like his brother in law, James Savage and other close associates from Winnipeg such as Sam Reynolds, city engineer for the city during Arbuthnot’s term as mayor.

Early in 1908, Arbuthnot acquired financing from a group of New York investors headed by Luther D. Wishart. The Pacific Coast Coal Mines Company was formed, their objective being no less than to buy out the Dunsmuir coal interests on the island. Arbuthnot made sure controlling interest in the company remained in the hands of the original Winnipeg group.

An article in the July 11, 1908 Montreal Gazette announced that “one of the largest deals ever put through on Vancouver Island is now in progress, the completion of which will mean the passing of the extensive coal areas controlled by Hon. James Dunsmuir into the hands of John Arbuthnot, ex-mayor of Winnipeg, and a number of New York millionaires of whom Luke Wishart is one.” The amount involved was upwards of $5,000,000 and Mr Dunsmuir had signified his willingness to sell. Mr Arbuthnot and other capitalists were now in Montreal.” Presumably they were meeting with representatives of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

In 1909 the Pacific Coast Coal Mining Company completed a railway line from Fiddick’s Junction on the E&N Railway line to Boat Harbour where their new docking facilities were located. The following year they completed the line to the Fiddick Colliery a mile and a quarter away passing under the E&N line as they were refused permission to cross the tracks. The new railway passed through what would become Morden mine, part of the extensive pre-emptors holdings acquired by John Arbuthnot and his associates in the Cedar area.

The Pacific Coast Coal Companies ambitious attempt to acquire the Dunsmuir coal interests on the island was dashed in 1910 when James Dunsmuir instead accepted a better offer from William Mackenzie and Donald Mann, railway builders of Canada’s second intercontinental railway, the Canadian Northern. The Dunsmuir Properties sold for $11,000,000 after the CPR allowed their option to expire. The February 10, 1910 issue of the New York times suggested that Mackenzie and Mann were financially backed by J.P. Morgan and J.J. Hill; United States railway giants, principals behind the Great Northern Intercontinental Railway just south of the Canadian border.

The new company formed to operate the former Dunsmuir interests, Canadian Collieries (Dunsmuir) Ltd was a direct subsidiary of the Canadian Northern Railway. Its President was William Mackenzie. Interest in Vancouver Island Coal was at its height with the anticipated completion of the Panama Canal which would open markets in the Pacific Rim to eastern Canada and Europe using Vancouver Island coal to propel their ships. The Pacific Coal Mining Company with its own docking facilities and huge coal reserves became extremely important to the far off movers and shakers in Eastern Canada. While they controlled the railway on the island through the CPR’s purchase of the E&N, they now needed access to coal reserves and docking facilities.

At the same time the owners of the Pacific Coast Coal Mining company were getting embroiled in lengthy court cases created primarily due to John Arbuthnot’s treatment of the New York shareholders. Consequently, in December 1912, Pacific Coast Coal Mines Ltd. was taken over by a group of Eastern capitalists from Montreal and Toronto under the name of Pacific Coast Collieries. John Arbuthnot and his Winnipeg “family” no longer had any say in the company.

And what did all these boardroom shenanigans have to do with those 19 miners who would not return home from work that fateful day a century ago? The numerous changes which took place within the ownership of the Pacific Coal Mines Company and subsequent changes in key personnel were a direct cause of the accident. It should have never happened.

The Discrepancy in Map Scales

Before discussing the actual details of the accident we need to look more closely at the location and circumstances of the South Wellington Colliery. The mine was bounded on the north by the abandoned Southfield mine and on the south by the abandoned Alexandra mine which were both flooded.

The Southfield mine was originally the property of the old Vancouver Coal Mining and Land company, predecessor of the Western Fuel Company and was in operation between 1883 and 1893. The Alexandra Mine was owned and operated by the Wellington Colliery Company (the Dunsmuir’s). It opened in 1884 and was abandoned in 1901. Actually the workings of this mine seriously encroached on the PCCM property; the Dunsmuir’s never recognizing the rights of the former pre-emptors of the surface to the underlying coal.

Pacific Coast Coal Mines on opening was well aware of precautions necessary when opening a colliery between two flooded mines. On January 30, 1908, then manager, George Wilkinson had applied to the Minister of Mines for copies of the plans of both adjoining mines which were on file with the Department. The “Coal Mines Regulation Act” at the time specified that plans could not be shown until ten years after abandonment without the written permission of the owner.

The owners of the Southfield mine through its general manager Thomas Stockett willingly provided permission even though the abandonment had occurred prior to the acquisition of the property by the Western Fuel company. Permission by the owners of the Alexandra Mine at the time, the Dunsmuir’s, however was refused.

The plans for the abandoned Southfield mine were drawn on a scale based on the older British measuring system using the Gunter’s chain. That is, the scale was 2 chains to the inch or 132 feet to the inch. The scale of the Fiddick mine however was based on the newer American system of surveying in feet; the customary scale being 100 feet to the inch. This scale for mine plans became embodied in the Statutes as the legal scale in 1911.

Chief Inspector Thomas Graham was aware that Pacific Coast Coal Mines had received the plans of the workings of the old Southfield mine as well as the scale of the older plan. When the plans were supplied to George Wilkinson on January 1, 1908, Graham was Superintendent of the Western Fuel Company and he was fully aware that the scale was at 132 feet to the inch. In fact he had ordered the draughtsman for the company at the time, Mr W. A. Owen to supply Mr Wilkinson with a blue print strip at a scale transmuted to 100 feet to the inch to comply with the plans of the Fiddick mine. This enlarged work was found in the possession of Pacific Coast Coal Mines after the accident. The scale was clearly marked on the original Southfield plan but was not shown on the blue print strip given to Pacific Coast Coal Mines.

Between 1911 and 1914 a great many changes took place in the official staff of the Pacific Coast Coal Mines. George Wilkinson who had been with the company since its formation resigned and John H. Tonkin was appointed General Manager in January 1913 when the reconstruction of the company took place. W. A. Owen, who had supplied the corrected blue print strip while in the employ of Western Fuel Company had gone to work for Pacific Coast Coal Company but in 1911 left this position also. Henry Devlin who was mine manager at Fiddick resigned early in 1913 to accept a position as a District Mines Inspector and was replaced by Joseph Foy. In January 1912 Thomas Graham accepted the position of Chief Inspector of Mines for the province.

With all these changes the corrected plan of the Southfield mine showing the scale at 100 feet to the inch got locked away in a drawer in the PCCM engineering office and it was the older Southfield plan done at the scale of 132 feet to the inch which was being used at the time of the accident. This in effect placed the abandoned flooded workings of the Southfield mine closer by almost 415 feet to the Fiddick workings than was thought.

Details of the Disaster

On the morning of February 9, 1915 at 11:30 A.M. in No. 3 north level off No. 1 slope it is believed David Nellest, Fire Boss, fired a shot which broke through into the old flooded workings of the Southfield mine. As a result of this inflow of water nineteen men lost their lives by drowning.

One miner, J. Murdock, after a hard struggle succeeded in reaching safety. William Anderson was working in No. 3 level and had succeeded in reaching the main slope. Remembering that his brother-in-law Robert Millar had been working further down No. 3 level, he at once handed his coat to his partner Gourlay and started down the slope where he came across a boy tending a winch and told him to run for his life. This the boy did which saved his life. That was the last seen of Anderson alive. Another miner, J. Bullich, thought to be one of the miners who were lost presented himself on February 12th at the company office to pick up his paycheck creating some astonishment to say the least. On leaving the mine he had gone straight home and not knowing the English language was not aware that his name was published on the list of those missing.

District Mines Inspector, John Newton received notice in Nanaimo at 12 noon on the day of the accident and immediately hurried out to the mine and took charge of operations as Mine Manager Joseph Foy was one of the victims. Foy had been on the surface but had gone underground intending to help the men reach the surface in company with Thomas Watson. On opening a trap door into the old slope, he was immediately met with a flood of water which hurled him against the timbers and trapped him there. Watson had already entered the flood and both were killed.

On reaching the mine and proceeding down No. 1 slope in company with J. C. MacGregor and John Piper, Inspector Newton found all avenues of escape had been cut off. The water had risen 600 feet up No. 1 slope above No. 3 North level where it had broke in. The water in the mine rose 25 feet vertically above the access to No. 3 North level.

The inspector ordered pumps installed immediately but some delay was experienced due to the creek from Beck’s lake caving in with the result that they had to divert the water from one creek to another channel. By February 11th, 3 pumps were installed and by February 16th seven pumps were in operation some being supplied by other mines in the area. It was found that with all seven pumps working, the water was only being lowered at the rate of 4 inches vertical a day therefore it would be at least seventy-five days before No. 3 level could be reached.

Inspector Newton had examined this area of the mine six days earlier in company with Manager, Joseph Foy. He had remarked that the places were very wet and asked how far they were from the Old Southfield mine. Manager Foy replied that the water was coming from and old swamp on their own property about 300 feet from their boundary line. He would add that there was a solid wall of coal between them and the old workings which were some 500 to 600 feet away and that he would show on a plan where they were in regard to Southfield on arriving at the surface. Back at the engineers office, Foy scaled the plan across, which showed a distance of 440 feet to the nearest place shown on the Southfield plan. He then told the Inspector that they proposed to run No. 3 North level up along the side of the boundary pillar and was told he must have bore holes ahead and flank holes to the side when they reached a distance of 50 feet from the proposed line. Manager Foy agreed to do this.

Back in November 1914, Superintendent of PCCM, John Tonkin had asked Chief Inspector Graham if there was any barrier-pillar law in the Province. He was told there was nothing in the Coal Mines Regulation Act to prevent him going to the boundary provided he left sufficient pillar between the eastward end of the Southfield workings and the place where he went across the boundary. Mr Tonkin said he would leave a 250 foot pillar which was acceptable to Mr. Graham.

Details of Enquiries and Subsequent Charges

On February 19th, Sir Richard McBride, the Premier, had announced in the legislature that a thorough inquiry into the disaster would be held. It would be sometime before the water was lowered enough to allow the recovery of victims at which point an inquest into the cause of the accident could be conducted. During the last week of April and early May they began to recover bodies from the mine and it was announced that the inquest would be held in Nanaimo on May 17th, 1915.

Chief Inspector Graham had been in Fernie at the time of the accident and on returning to Victoria found that Inspector Newton had forwarded to the Department a blue-print he had received from Mr. Tonkin. He immediately realized that the company had been using on their most recently made mine plans a direct copy of the adjoining Southfield mine (to a scale of 132 feet to the inch) instead of the enlarged plan of 100 feet to the inch. If a proper enlargement of the Southfield mine plan had been applied to the PCCM plan it would have shown the true location which brought about the fatal results.

Although Chief Inspector Graham at once realized the cause of the disaster he did not feel justified in making this information public without the confirmation of a resurvey. He verbally informed the Minister of his beliefs and also of the impossibility of actually proving his suspicions. It was decided that such suspicions not be made public until after they were verified by actual surveys by a competent mine surveyor and that an investigation be held under the “Public Inquiries Act.”

At the Coroner’s inquest held in Nanaimo on May 17th, Chief Inspector Graham announced at the opening of the decision to have a survey done as soon as the mine was un-watered followed by the investigation under the “Public Inquiries Act.” He did not however deem the plans important to the Coroner’s inquest.

The Nanaimo paper reported the verdict of the inquest the following morning

“We your jury return a verdict that Thomas Watson, Robert Millar and seventeen others met their death by drowning through the flooding of South Wellington mine on the 9th day of February, 1915

We are unable to place the blame at present on any party or parties but would strongly recommend that the Provincial government take immediate steps to have a re-survey taken and hold a rigid examination and if possible ascertain who is responsible for the lamentable catastrophe and place the blame on the right parties.”

The survey carried out by D. B. Morkill, BCLS on May 25th confirmed that the surveys of both mines were substantially correct which left no doubt that the accident was caused by the improper use of a direct copy of the Old Southfield plan, instead of the enlargement which complied with the PCCM plan.

Commissioner Justice Murphy was appointed to hold a Court of Enquiry under the Public Enquiries act which was held at Nanaimo on the 5th, 6th, and 7th of July 1915. The scope of the commission was to enquire into the cause and responsibility of the accident, into the plans and workings of the mines and generally into conditions existing at the two mines at the time of the accident. Mr Tonkin was the only witness on the first day while Thomas Graham was the principal witness on the last day. He was subjected to a severe cross-examination by counsel representing relatives of the victims and was criticised by Commissioner Murphy for suppressing evidence at the inquest in allowing plans to be presented which he knew to be wrong.

Mr Justice Murphy submitted his report, a 48 page document at the conclusion of the enquiry. On the matter of the main issue, he reported:

“The responsibility for the South Wellington disaster on Mr. Graham’s part is, however, purely negative. He is to blame, not for what he did, but for what he did not do, and what his official position made it his duty to do. Mr Tonkin played the active role. With the full knowledge that Mr. Graham was leaving everything to him, that he, Mr Tonkin, proposed to remove the 100 foot barrier wall right up to the boundary and then turn and run west directly towards the supposed location of the old Southfield workings again, to his knowledge long abandoned and partly filled with water, and with the further knowledge that he must have had as manager that water was freely flowing into the South Wellington No. 3 north level 300 feet down from the face, which water might be from a surface swamp and might be – as turned out to be fact – from the old Southfield workings, fully aware in addition that error meant death in all probability to many miners, what did he do? He proceeded to South Wellington to inspect the data and come to a decision (he did not reside at the mine, but usually visited it once a week). He was aware that at Nanaimo, 4 1/2 miles distant the original map of the Southfield workings was open to inspection in the office of the Western Fuel Company. Instead of obtaining it, he had Wright produce, he says, Exhibits 2, 4 and 7 – Wright says Exhibits 2 and 1 – superimpose them, and on this he decided……The main fact in this connection is that Mr Tonkin knew he could have access to the original Southfield map at the office of the Western Fuel Company at Nanaimo, 4 1/2 miles distant. Instead he used copies, and copies which, on their face, considering the problem being decided, ought to have aroused suspicion. On him, in my opinion, reads the direct primary responsibility for the accident”

Base on Mr Justice Murphy’s report and after full consideration by the Executive Council, Attorney General W. J. Bowser initiated proceedings for the prosecution of Mr. Tonkin and Mr. Graham on the charge of manslaughter. In the preliminary hearings conducted September 24 and 25, 1915 before Stipendiary Magistrate Kirkup, the Tonkin and Graham cases were judged separately. Testimony was heard from many sources. W. J. Taylor counsel for Mr Tonkin and E. V. Bodwell, counsel for Mr. Graham made strong pleas for dismissal of the two, contending that there was no evidence whatever to warrant such charges.

Magistrate Kirkup said that in a serious matter of this kind he did not feel justified in dismissing such a serious charge and considered the evidence sufficient to commit the accused for trial by a higher court.

The finding of the Grand Jury at Nanaimo held October 27, 1915 cleared both John H. Tonkin and Thomas Graham of all legal responsibility for the disaster in South Wellington the previous February. At the opening of the assizes, Mr Justice Clement told the jury that they were the “most irresponsible body known in law.”

Within two years of the accident, Pacific Coast Coal Mines ceased all production at the Fiddick mine and moved all workers to the newer Morden Colliery approximately 2 miles to the east. By 1922 the company was in bankruptcy and went out of business entirely.

On April 5, 1917 Thomas Graham resigned as Chief Inspector of Mines and ironically was replaced by the original General Manager of Pacific Coast Coal Mines, George Wilkinson. John H. Tonkin returned to Salt Lake City in the United States. His heritage home in Oak Bay is now part of the Oak Bay Library.

A further note of irony considering the error which produced the South Wellington disaster. The Metropolitan Building in downtown Victoria which housed the executive offices of the Pacific Coast Coal Mines Company would later become the offices for the Corporation of BC Land Surveyors.

Note: We will be adding a list of victims along with a brief glimpse of their bios in the near future

by: Rick Morgan

Sources:

- Annual Report of the Minister of Mines 1915

- British Colonist online newspaper

- New York Times online newspaper

- Sessional papers of the Dominion of Canada 1916. Summary report by Joseph G. S. Hudson Mine Accident at South Wellington BC

- Nanaimo Daily Herald clippings supplied by Helen Tilley.